The Street Vendors Act, 2014 defines a 'street vendor' as "a person engaged in vending of articles, goods, wares, food items, or merchandise of everyday use, or offering services to the general public, in a street, lane, sidewalk, footpath, pavement, public park, or any other public place or private area, from a temporary built up structure or by moving from place to place, and includes hawker, peddler, squatter and all other synonymous terms which may be local or region specific”.

The Act identifies two categories of vendors, stationary and mobile vendors. “Stationery vendors” are defined as street vendors who carry out vending activities regularly at a specific location and mobile vendors as street vendors who carry out vending activities in designated areas by moving from one place to another place vending their goods and services.

The street sellers provide vital services that must not be overlooked. They serve as an efficient and effective distribution channel between producers and consumers, delivering goods to one's doorstep at significantly lower prices than those in traditional markets.

Their presence assures a more comprehensive range of options at reasonable rates and increased convenience for the average person. Given the low capital investment and mobility, street vending is an effective way of catering to seasonal and sporadic demands.

The definition of street vendor is broad but vague. The implementation of street vending law focuses only on the existing vendors who sell their products and services on the city's streets, within the limits of their jurisdiction. However, some mobile vendors sell their products at railway stations and on trains and those who sell products at door steps. Though the more significant definition of street vendor under the Act covers every vendor who vends in private or public places, the definition of mobile vendor narrows down the definition to those who carry out vending activities in designated areas by moving from one place to another place. However, the survey mandated under the Street vending Act 2014, by the local self governments does not cover the above categories as they are outside the municipal jurisdictions.

As part of preparing a draft street vending plan for Alappuzha Municipality and a relocation plan for Kochi Municipal Corporation by CPPR, the team visited both places to understand the existing conditions of Street vending. The field survey to districts of Alappuzha and Cochin in Kerala shows that there are instances where the fishermen sell the daily catch on the road sides of these coastal districts of Kerala. However, the local governments are not identifying them as street vendors. The local authorities cited practical difficulties in providing vending licences to the fishermen for two reasons. First they do not sell regularly and second, iit is not the same fisherman who sells regularly. Thus they cannot get the rights guaranteed to a street vendor.

Further, some businesses adopt street vending models for their shops, with temporary structures eg. Chaiwallah which is a chain of tea vending spread over different cities in Kerala. While a plain reading of the definition of street vendors includes them, the other criteria to qualify as a street vendor in the Street Vending Act and Rules disqualify them from being regulated under the law. Chaiwallah operates on a franchise model that is not accepted under the street vending law , that previews street vending as an essential primary livelihood option. There is a gap in which law regulates these businesses that adopt street vending characteristics.

Moreover, street vending is commonly seen in urban and semi-urban areas of India. However, there are vendors in rural areas that come under the jurisdiction of panchayats. However, the Act defines local authority as Municipal Corporation, Municipality, or Nagar Panchayat or any Civil authority appointed to provide civic services and regulate street vending. It also includes the “planning authority” which regulates the land use in the city or town.” Thus, even when the Act gives a broad definition to street vendors, it seems the Act's provisions and rules and schemes apply only to those vendors who sell on the streets under their municipal jurisdiction. No power is given to the local authority to bring in a region based definition.

Street Vendors can be characterised into four main categories, to issue the certificate of vending.

Figure 1: Categories of street vendors

Stationary Vendors: Street vendors who regularly operate their businesses from a set location and transport their merchandise, pallets, and other necessary items to the vending place with human effort of only one person are referred to as stationary vendors.

Mobile Vendors (without motor vehicles): Vendors who offer goods or services while walking, carrying their load, or operating hand- or pedal-powered vehicles that are exempt from registry under the Motor Vehicles Act of 1988, do not presently require a licence to operate.

Mobile Vendors (with motor vehicles): Vendors doing any vending business employing motor vehicles of any type, the operation or movement of which needs a licence under the Motor Vehicles Act of 1988.

Other categories of vendors: The concerned Town Vending Committee shall also identify other categories of street vendors, such as vendors in weekly markets, heritage markets, festival markets, and night bazaars, who may be doing business within the jurisdiction of the said committee, and shall provide for the integration of such vendors or a separate facility for such vendors to continue their business.

The vending categories can vary according to the said divisions, for example several vendors move from region to region depending on growth and fall of seasonal businesses. During festive seasons, vendors from around the region temporarily consolidate in specific areas to attract more customers and grow their businesses. They can be considered as temporary or seasonal vendors but they have not been given a criterion in the rules. The TVC could have a mandate to also provide a temporary licence to such vendors who vend on a seasonal basis. TVC may categorise the other vendors into two broad categories: seasonal and weekly vendors and fix a vending fee based on the vending period of the area occupied by them.

Moreover, a few cities in Kerala , have failed to differentiate between categories of vendors such as the mobile and stationary vendors. The categorisation is essential as the law defines the two categories separately, which helps in smoother implementation of the law. The vending fees, the rules regarding movement and designation of vending zones differ from stationery to mobile vendors. The failure of municipal governments in categorising the vendors act as a hindrance while allocating spaces to the vendors by duplicating the space for stationery and mobile vendors. The mobile vendor need not be allotted a space according to the street vending laws. Instead they must get approval from the traffic police and the town vending committee for moving around in the city.

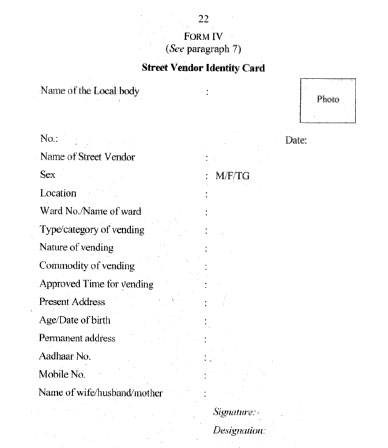

Moreover the ID card to be issued to the vendor according to the Kerala Scheme 2019 has to record the vendor's location, wherein mobile vendors move from place to place. They should be allowed to operate in the city limits by the local authority, rather than specifying the location /ward in the Identity Card or Vending License.

It is apt to have ID cards with different colours that differentiate the category of vendors as stationary and mobile for smoother implementation.

The licence for street vending shall be issued on the following conditions:

Fig 1 : ID card given in the Kerala Scheme for Street Vending 2019.

Issuing licence for vendors is a complicated affair because street vending is a very heterogeneous business model across the country. Many times, identifying whether an individual holds more than one street stall or has another business, or recognizing whether his/ her family members are the one who operates the street cart are practically tricky. There are cases where hawkers are hired on a salary basis and are provided with goods to sell on the streets. These models can continue by manipulating the authorities, when there are too many criteria without proper monitoring mechanisms in place 5 (The New IndianExpress, April 2022).

Furthermore, some individuals and groups take licenses or permissions using the ID cards of different individuals and give them salaries for doing street vending businesses for them. The profits are then taken by these groups. Just laying out specific criteria for street vending license is not enough, there has to be a mechanism under TVC that includes vendors in each ward in identifying the genuine beneficiaries of the law.

The criteria mandating that an individual must not be the legal heir of someone who already holds a Certification of Vending within local authority's jurisdiction violates the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. The right to freedom of profession and trade under Art 19(1)(j) allows a citizen of India to engage in a trade or profession of his choice. While an individual is not allowed to vend on streets to earn a livelihood with minimum investment, the law is curbing the fundamental right entrusted by the Indian Constitution. Moreover, in a state with 64,006 impoverished families, accounting for 0.64 per cent of the total population6 a law restricting the opportunities to start a livelihood with a minimum investment is irrational.

At times, the authorities' bias also comes into the picture as they refrain from giving licence to migrant workers. However, the reality is that cities with higher populations do not even have sufficient holding capacity to accommodate the local vendors, due to which they do not give licences to migrants. For this reason, illegal vending by migrants is a common site across cities. There is no mention about the eligibility of migrant workers to do vending, as a uniform law across the country. It is up to the local authorities to have these clauses in their byelaws.

5 - “Street Vending Zone: Kochi Corporation Senses Foulplay.” n.d. The New Indian Express. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/kochi/2022/apr/14/street-vending-zone-kochi-corporation-senses-foulplay-2441727.html.

6 - https://www.onmanorama.com/news/kerala/2022/03/14/lsg-survey-extreme-poverty-kerala.amp.html#:~:text=Thiruvananthapuram%3A%20Kerala%20has%2064%2C006%20extremely,population%2C%20a%20survey%20has%20revealed.

The Town Vending Committee shall follow the following criteria for issuing of Certificate of Vending:

The law prescribes that ‘preference’ would be given to those belonging to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes, Women, Persons with Disabilities, Transgender and Minorities, if the vending space does not match with the holding capacity. It is unclear as to how the preference will be given among SC, ST, OBC and disabled and minorities, except generic guidelines as to identify the uniqueness of the type of vending. To ensure fair opportunity, the Town Vending Committee should be clear about how the preferences should be given by laying down proper guidelines for issuing licences.

To maximise the holding capacity of an identified vending zone, TVC can also adopt measures like time sharing basis by providing movable kiosks to include more vendors in the identified vending zones.

Another option would be to customise the kiosks provided for each type of vending in the designated vending zones by limiting the area of each kiosk. For instance, those who sell lottery tickets and betel leaves may be provided with a kiosk of smaller size (10sqft). This can help in accommodating more vendors. The Kerala Scheme 2019 suggests collecting extra fees from vendors occupying more space than the maximum size allowed , ie. 25 square feet. As fees are not that high,vendors will apply for more space. This may create issues regarding space allocations in places like Cochin where the holding capacity is less compared to the number of vendors. The TVC can consider the applications for more space on a case to case basis and allocate a large kiosk to those who require the same based on the commodity they sell.

The vending fees for the various categories shall be fixed as follows:

| Category of Street Vendors | Area | Vending fee |

|---|---|---|

| Stationary Vendor (fulltime) | Upto 10 square feet | 1% of the guideline value subject to minimum of 750 Rs per annum |

| 10 to 25 square feet | 2% of the guideline value subject to minimum of 1500 Rs per annum | |

| More than 25 square feet | 3% of the guideline value subject to a minimum of 3000 Rs per annum | |

| Stationary Vendor (part time or time sharing) | Upto 10 square feet | 0.5% of the guideline value subject to a minimum of 375 Rs per annum |

| 10 to 25 square feet | 1% of the guideline value subject to a minimum of 750 Rs per annum | |

| More than 25 square feet | 1.5% of the guideline value subject to a minimum of 1500 Rs per annum | |

| Mobile Vendor (with motor vehicle) | Upto 10 square feet | 750 Rs per annum |

| 10 to 25 square feet | 1500 Rs per annum | |

| More than 25 square feet | 3000 Rs per annum | |

| Mobile Vendors (without motor vehicles) | Upto 10 square feet | 375 Rs per annum |

| 10 to 25 square feet | 750 Rs per annum | |

| More than 25 square feet | 1500 Rs per annum | |

| Mobile Vendor (headload) | 250 Rs per annum |

Table 1: Vending fees for the various categories of vendors

The vending fees is determined by classifying the vending zones into three categories

- Primary Zone, - Secondary zone and, - Tertiary zone

The vending fees for tertiary zones are given in the table above. The vending fees for secondary zones is twice and primary zones will be thrice the fees of tertiary zones.

In the Rules for the Street Vending Act in Kerala, the ‘guideline value’ is used as the index deciding the fee the stationary vendor must pay to the local authorities. The phrase 'guideline value’ is not defined in the Street Vending Act, Kerala Rules 2018 or Kerala Scheme 2019. Thus, the municipality and municipal corporation are tasked to define the term in their bye laws. The definition adopted by the urban local self government acts as the benchmark or standard on which vending fees are determined and collected from the vendor.

A uniform definition is not logical as the commercial potential of the vending area is different in different cities in Kerala. The town vending committee that included representatives of street vendors must recommend the “guideline value” in the area under their jurisdiction. One of the methods to solve this can be by calculating a typical standard vending cost by considering the area occupied and the commercial potential of the area by the vendor as a criteria. Furthermore, the guideline value shall not be prohibitively dearer for the vendor.

The Certificate of Vending is valid for three years from the date of issuing or until the following vendor enumeration, whichever is earlier.

Although there is clarity on the duration of the street vending licence, there is no clarity on how to deal with vendors who do not use their space after a certain period. During field visits in Alappuzha and Kochi, it was observed that there are vending carts which are kept closed for a while. On enquiring to nearby shopkeepers, it was known that many vendors have stopped vending due to the fall in business during covid time. However, their carts are still left in a public space which occupies the space that could ideally be given to another vendor. There needs to be clarity on how long such a vendor could hold the space to himself. Periodic assessments should be conducted to understand whether all vendors are utilising the space. TVC can conduct bi-monthly meetings with vendors to identify unused spaces and issue notice to the vendor concerned for explanation after verification.

According to the Kerala Rules, a survey must be done every five years. The Town Vending Committee has to review applications' invitations. However, this process can be done more regularly and with rigour as applications for vending can come in, between these five years. A congruence between the renewal period and new surveys for accepting newer applications can help the smoother implementation by revoking licenses of those who do not use the vending space allocated and issue the same to another vendor who is needy.

On checking the Certificate of Vending (COV) of vendors located in Kochi, Kerala, it was found that their COV does not include the zone allotted to them. Ideally, a COV should contain the vendor's location so that there is proper evidence favouring the vendors, if any issue arises. The Municipality could relocate them to any area if there is no proper documentation.

The Certificate of Vending can be revoked or suspended under the following circumstances:

No Certificate of Vending will be revoked until the owner has been issued a notice giving him 15 days to respond to the accusation that the certificate is being proposed to be cancelled. The 15-day timeframe begins when the notice is served on the seller or given to his last known address. Due procedure must be followed before the suspension of the certificate of vending.

A Certificate of Vending may be suspended for a fixed time period for any infraction of the certificate's terms that is correctable during the suspension period.

The Food Safety Department has every right to cancel or suspend registrations but street food stalls issue a statement claiming their income is below a particular figure. So the review procedure is not as stringent. When an officer visits a specific area to inspect a hotel or a food processing unit, he or she drops by thattukadas in the vicinity to check cleanliness standards.

No notice to be given in case of suspension of the certificate of vending for less than 7 days, to prevent commission of an act detrimental to public health and order.

The grounds of revocation specify that law intends to allow street vending as an essential primary livelihood option for those who have no other livelihood or earning for survival. Thus the law negates the option of an individual to have street vending as a business model with multiple vending spaces.

The concern of certificates to vendors also depends on how long they occupy the space. During off seasons and when the vendor leaves the space, the vendor leaves the kiosk in the allotted space. Because vending used to be an unorganised sector for a long time in most parts of India, the new rules and schemes may be unclear or confusing for many vendors who have been in the street for a long time. There needs to be a system where these concerns can be clarified and communicated rigorously to every vendor. The FSSAI license requirement being mandatory must be communicated to the street vendors by TVC as many come from a poor educational background. Ignorance of the conditions, may lead to arbitrary revocation of the vending licences.

The TVC must come up with some provisions in the bye laws where they can allocate the space unused by a vendor for 6 months in a row, to a new applicant. The information regarding unused licences and spaces may be collected through a participatory approach through frequent TVC meetings.

One criterion for revoking a certificate is that if the vendor has constructed a permanent structure, this may not be applicable for zones for mobile vendors or for those vendors located in zones where the local authorities have built permanent or semi permanent structures.

The vendor has no right to choose where they will be relocated. This can affect their business activity, as the footfall may decrease and that inturn may negatively affect the potential profit they will face once they move to a particular space. The vendor has a clear understanding of the locality they do vending in. Locations for shifting the vendors have to be selected after thorough study and analysis by urban experts and taking into confidence the vendor’s community. An example of poor relocation strategy is the relocation of vendors in Pondy Bazaar in Tamilnadu. The street vendors were relocated from the street to dedicated space, resulting in lower income for the vendors.

“Shahul Hameed of Nifasha Footwear says he sold just one pair of slippers on Tuesday. “I used to make at least Rs. 2,000 every day when my shop was on Pondy Bazaar Road,” he says. 7 (The Hindu, 2014)

The local authority can collect maintenance fees from the street vendors , apart from the vending fees, for provisioning the civic amenities such as drinking water, waste collection and disposal. The fees can be decided under the bye-laws drafted by the local government. There is no criteria fixed as to determine the charge to be fixed as maintenance fee. The Kerala scheme specifies that every street vendor remit maintenance charges to local authority as and when levied from the other shops. Hence they are seen as equivalent to other shops, regarding levy of maintenance charges.

Street vendors belong to the unorganised sector, however the Act of 2014 or Kerala Rules of 2018 and Schemes of Kerala of 2019 do not cover much on the aspect of social security of street vendors. Ensuring such provisions could help avoid harassment or intimidation from the local administration or police. Apart from social security, a bonafide welfare program that can be promised to the vendors will help them during times when certain businesses do not prosper, or during natural calamities, epidemics/pandemics, and temporary displacement as part of construction or development.

7 - The Hindu. 2014. “Business Dull for Pondy Bazaar’s Relocated Hawkers,” May 21, 2014, sec. Society. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/chennai/chen-society/Business-dull-for-Pondy-Bazaar%E2%80%99s-relocated-hawkers/article11625129.ece.

On the recommendation of the TVC, the local authority may declare a zone or part of it a no-vending zone for any public purpose and relocate street vendors vending in that area in the manner specified in the state scheme. According to the Kerala state scheme, relocation will require TVC approval and be to a neighbouring area or the same locality.

2. The local authority may also evict vendors who lack a vending certificate (under section 10) or vend after the expiration of the vending certificate. Such vendors shall be given a 30-day notice to evict such a location. As per the Kerala state rules, immediate eviction will be done in cases of no certificate or vending in a no-vending zone. The local authority can evict or relocate such vendors physically. Suppose the vendor is discovered vending after the notice period. In that case, they will be liable to pay a fine of up to two hundred and fifty rupees, not exceeding the total value of their goods as determined by the local authority.

Many cities do not consider street vendors' problems when preparing master plans. The infrastructure development projects which come forth as a part of the city development could lead to the displacement/ relocation of the street vendors if they are not considered in the planning process.

In many cases, vendors are uncomfortable with the relocation sites identified by the Municipalities. The town vending committee has the final call to approve the newly allocated zones for vending. During the field research in Alleppey (Kerala, India), it was discovered that there was a miscommunication between departments on the new proposed zones, and they were not accepted by the vendors and the unions representing them as it was not feasible for business. Most of the proposed zones were areas with less footfall and a zone inside a gated compound. This shows how the principles of a street plan are not entirely looked at. Street vendors form a part of the streets and have to be permitted to sell on the streets and not secluded areas.

Relocating vendors is not essentially an act welcomed by them. Vendors might have been vending for decades in a particular area and form a part of the character of the street. Moving these vendors would cause agitation and make them feel they do not have the right to the city.